To the roots of female photographers of artistic nudes: Anne Brigman

Foreword

I had intended to discuss Diane Arbus next, having noted her work at nudist camps, as described on online resources. However, deeper research revealed that while Arbus did photograph nude subjects, her approach represents something categorically different from the aesthetic tradition we've been exploring. Where Bernhard (and every other photographer treated here untill now) sought transcendent beauty in the female form, Arbus sought to document human diversity without hierarchy or idealization. Her nudist photographs are anthropological, photo-journlistic, rather than aesthetic—important work, but belonging to a different conversation about documentary and social photography. Therefore, I'll turn instead to Anne Brigman, whose work continues our exploration of the nude as a vehicle for beauty and formal investigation.

Biography

Anne Nott was born December 3, 1869, in Nuʻuanu Pali above Honolulu, Hawaii, from American missionaries. In 1885, at age sixteen, her family moved to Los Gatos, California. In 1894 she married Martin Brigman, a Danish sea captain twenty years her senior, and settled in Oakland, California. She accompanied her husband on several voyages to the South Seas but ceased traveling with him around 1900, establishing permanent residence in Oakland where she worked in a shared darkroom on Brockhurst Street.

Brigman began photographing in 1901. Her first public exhibition came in January 1902 at San Francisco's Second Photographic Salon, where her "Portrait of Mr. Morrow" received critical attention in Camera Craft magazine. Within two years she had established herself as a master of pictorial photography. Following success at the 1903 Third Photographic Salon, she opened a teaching studio in Berkeley.

In late 1902, Brigman discovered Alfred Stieglitz's journal Camera Work and initiated correspondence with him. By 1903 she was listed as an Associate of his Photo-Secession; she became an official Member in 1905 and achieved Fellow status in 1908 — the only photographer west of the Mississippi so honored. Between 1903 and 1908, Stieglitz exhibited her work frequently and published her photographs in three issues of Camera Work. The Secession Club held a special exhibition of her work in New York in 1908.

Her recognition extended internationally. The Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh and the Corcoran Art Gallery in Washington, D.C. both staged solo exhibitions in 1904. In 1905 her photograph "The Vigil" appeared at the London Salon. She was elected to the British photographers' Linked Ring and exhibited at its 1908 Salon. Her image "The Kodak — A Decorative Study" won the cover position of the 1908 Kodak catalogue. In 1909 she won a gold medal at the Alaska-Yukon Exposition. She exhibited at the landmark 1911 International Exhibition at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in New York.

In the Bay Area artistic community, Brigman became close friends with writer Jack London, poet Charles Keeler, painters Arthur and Lucia Matthews, and landscape artist William Keith. In 1908 she performed the lead role in Keeler's play "The Will of the Wisp" at Berkeley's Hillside Club. Between 1904 and 1908 she exhibited extensively throughout California at venues including the Oakland Art Fund, Berkeley Art Association, and galleries in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Monterey.

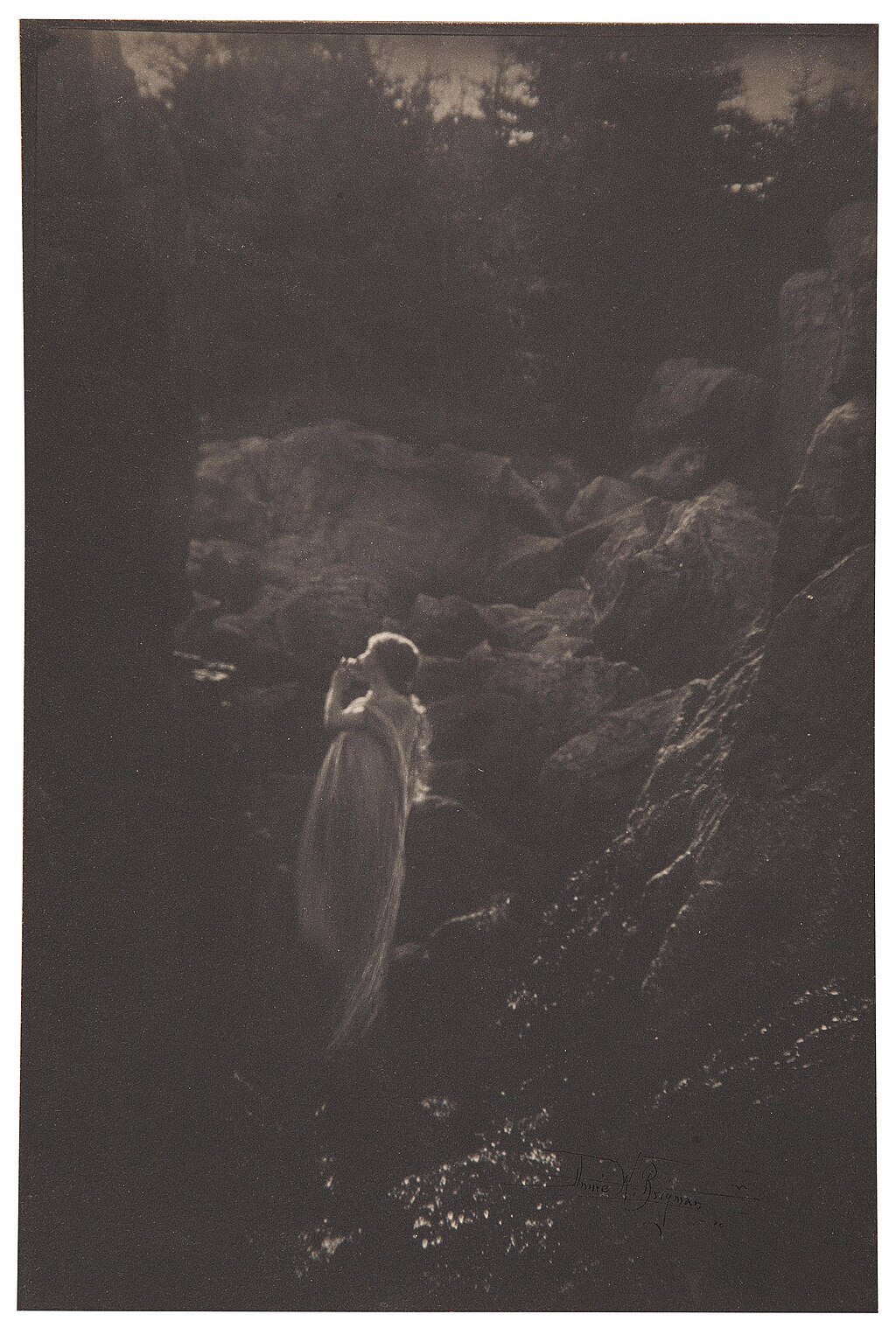

After the devastating 1906 San Francisco earthquake, Brigman began making frequent photographic expeditions to the Sierra Nevada, working at elevations around 8,000 feet at locations including Donner Pass, Echo Lake, and Desolation Valley near Lake Tahoe. These mountain journeys produced her most iconic work: nude figures merged with ancient trees, granite formations, and mountain landscapes.

In 1910, Brigman traveled to New York for eight months, where Stieglitz had promised her a solo exhibition at Gallery 291 — a promise that went unfulfilled. She found the atmosphere at the gallery's discussions of sexuality and the female nude deeply at odds with her own artistic philosophy. That summer she attended Clarence White's inaugural photography summer school in Maine. Upon returning to California, she and her husband separated (though never officially divorced). By 1912 she had converted a structure on her Oakland property into independent living and working space she called her "cave."

A June 1913 interview in the San Francisco Call featured Brigman discussing women's liberation and her separation: "He had his way of thinking and I had mine, and we developed along different lines. So now I am here working out my destiny." She declared that photography offered her "freedom of soul, emancipation from fear." By 1915, her colleagues considered her a leader in the Bay Area artistic community, and she wrote art criticism for local publications.

Between 1908 and the mid-1920s Brigman frequently vacationed in Carmel-by-the-Sea, where she exhibited at seaside salons and studied etching under James Blanding Sloan, exhibiting etchings in 1925 at Berkeley's League of Fine Arts. Throughout the 1920s she displayed her "imaginative nudes" at International Exhibitions in San Francisco's Palace of Fine Arts and Palace of the Legion of Honor. She worked with Francis Bruguière on the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition photography exhibition.

In 1929, at age sixty, Brigman moved to Long Beach, California. Declining vision led her to abandon professional freelance photography in 1930, though she continued photographing through the 1940s. Her work evolved toward straight photography and near-abstract studies of sand patterns and vegetation. In the mid-1930s she began taking creative writing classes, and poetry became her dominant form of expression.

She compiled two manuscripts pairing poems with photographs: Wild Flute Songs (unpublished) and Songs of a Pagan, which found a publisher in 1941 but wasn't printed until 1949 due to World War II. Stieglitz wrote a special introduction for Songs of a Pagan in the form of a letter declaring her important contributions to photography.

Anne Brigman died February 8, 1950, at age eighty, at her sister's home in El Monte, California.

Approach

A long and quite adventurous life our heroine lived, starting from the Victorian era which surely had other ideas in mind about what women should do with their lives. But her marriage years traveling by boat with her husband gave her a sense of freedom and independence that nothing afterward could break.

Immersed in the Oakland-Berkeley area at the beginning of the twentieth century, she entered photography in its Pictorialist form, as in previous articles said, dictated by various factors and gear limitations too.

High up in the Rocky Mountains she realized images of herself, her sisters, or friends to impersonate mythical creatures inspired by ancient Greek-Roman culture, inscribing her work in the wider romantic movement that at the start of the twentieth century opposed the positivism and technologist visions. A movement vast as the English-speaking world, considering that the echoes of those images were nurtured even in England and Ireland in the aftermath of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Her outdoor performances with friends as nymphs and dryads echo the romantic medievalism that swept through English-speaking artistic circles — from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood through William Morris's Arts and Crafts movement, extending even into the mythopoeic literature of Lord Dunsany and later Tolkien. All shared a rejection of industrial modernity in favor of an enchanted, pre-Christian relationship with nature. This cultural current flowed directly into the Bay Area bohemian scene where Brigman found her artistic voice.

In Nature, on top of a cliff, contextualized with a gnarled or lightning-struck tree, the feminine figure transcends to a spiritual state, not only through feminine beauty, but also because of the struggles a body has to endure in the harshness of the world. This is the key to the contrast with Stieglitz: for him, influenced by Freudian theories, her nudes represented sexual liberation and erotic energy. For Brigman, woman and nature together were not merely to be admired for their beauty, but to be revered for the strength they display in their fight to grow and flourish no matter what, even against the winds of time and entropy.

Conclusion

Astonished even this time, I feel in this life and career a link to my personal biography.

Once upon a time, in several other lives I personally had, I have been a mountaineer and a trekker too. I consumed my knees in my teens exploring Mount Etna and other Sicilian naturalistic beauties, then I went to various natural parks in Abruzzo, Campania, Liguria, Toscana, with WWF or with friends of the time.

In an afterward life I have been an editor in a pair of web magazines about Fantasy literature. Personally, I discovered the novels by J.R.R. Tolkien and as a response I felt the urge to understand how he made his fantastic world, so I analyzed deeply his biography and his medieval mythological preferred readings.

Then I discovered and appreciated too William Morris, read his The Well at the World's End, Lord Dunsany's Gods of Pegāna and The King of Elfland's Daughter (among many other works: the Kalevala, the Edda of Snorri and the Poetic Edda, Early Irish Myths and Sagas, etc.).

It has been a dream era for me in my coming-of-age times, and now I see works from her like The Bubble, The Breeze, but above all Soul of the Blasted Pine and the meaning that I can read in it: through ravine, past struck shapes of me and of my life I rise again in spirit.

Such was her Art.

This is too my very own call to Art.

One can ask, I suppose, why didn’t I ever perform an artistic nude session in a wilderness context? Oh well it is a logistic and economic issue: living next Milano city is good to find models, but is very afar from the first less crowded portion of naturalistic territory. Also, it would cost more, so that even if this type of images is very in tune with myself in this beginner part of my art career, were I am still fighting to make this business economically sustainable, I can’t afford such a production.

Nothing says, though, that I will never do shootings like these. Give me time and sales and Patreon support, and you will see what will be my personal interpretation of this imagery!

Shine on!

Per aspera ad astra!